|

Principal path =Home >Ancient Beads>The Oldest Beads> Beads and Technology

Bead Revolutions: The Role of Beads in Technological Change

paper read at Bead Expo 2000 by Pete Francis

People want things. They like to possess things. They like to keep them. People have a desire to have things.

This is known. Whole books have been written about the phenomenon. What is not understood is why people want to have things. I am not going to try to answer the why question. My remarks are concerned with the how and wherefore.

Cast your mind back to the time when there was no place to put things: no pockets or purses; no saddlebags or shelves. How did you keep something? You got a hole into it and strung it up to wear around your neck, ankle or wrist or to sew it onto clothes.

Thus was born the humble bead.

Beads have been around for a long time. So long that they were almost invisible. That is beginning to change. Scholars and non-scholars are recognizing the value in studying beads. I think we have just begun to reap what we can learn from them.

Now think of keeping all your treasures on a string or sewn to your clothes. What would you keep? Something attractive, rare, colorful, lustrous, unusual. Something that says to the world, "Aren't I cool? Don't I look fine?"

Thus was born the notion of precious materials.

The value of beads, I contend, led to a number of developments in prehistoric and historic times. Some of these developments were critical in the progress of the human race. I'll present four such cases.

1. Exploration

Many early bead materials came from somewhere other than the area that archaeologists find them. Dr. [Randall] White told us earlier this morning that bead materials in ancient European sites often traveled hundreds of kilometers.

|

Here is one of the earliest beads in Asia, some 20,000 years old. It is an Oliva shell that has been ground at the apex and gouged through the final whorl. It was found at a site in India and would have required a trip of about 200 miles (300 km) to bring it from the nearest marine source, and that is if you could fly. Walking doubles that.

We don't know how it got to the site, through trading or gifting or someone going to the sea to bring it back.

|

|

|

|

So, too, with one of the oldest beads in the Americas. This marine shell bead comes from Lindenmeier, Colorado from some 11,500 years ago. It is over 800 air miles (1300 km) from the nearest possible source.

It is so well polished, no doubt from use, that I could not see any abrasion marks from its manufacture under a microscope.

|

|

So a few beads traveled a long distance. What's the big deal?

|

|

Well, it's more than that.

The word used for bead in the greatest number of languages in the world is the same word used for pearl. This is true in Greek, Latin, French, Italian, German, Swedish, Serbo-Croatian, Hindi, Tamil and languages of insular Southeast Asia. Of course, it is not the same word, but the word for pearl is the word for bead.

Pearls are conceptualized as the original beads.

|

|

In Russian, Czech, Polish, Dutch and Yiddish the word for bead is the word for coral.

Both words are widely used for beads. But where do the substances come from? From the bottom of the sea! Why would anyone ever go there? You don't fish at the bottom of the sea. All you do is dive for bead materials.

|

|

|

|

Nor is it just diving. Consider the case of lapis lazuli. The only known ancient source is in a desolate valley in Badakhshan, Afghanistan, where no one lives.

Yet for at least 6500 years people have gone there in the summer, built fires along the cliff faces, thrown cold water on the rock to shatter it and extracted the blue stone. It was sent to Mesopotamia (now Iraq) as early as 4500 BC.

|

|

My point is that people wanted precious things to make into beads and explored much of the Earth's surface (and even the sea floor) to get them. We know this is why the Spanish came to America. They were looking for gold, coral and rubies. They found mostly silver, turquoise and jade, but that was rewarding enough for them.

We know that the Pharaohs of Egypt built cities in the Sinai desert occupied only for a few months of the year to extract the turquoise there.

Much of the face of the globe was discovered out of a desire to get bead materials.

2. Extracting and Synthesizing

One day someone discovered a shiny, metallic rock. It wasn't any good for chipping into a stone tool, but when s/he brought it home, the rock could be pounded into shape or heated and formed.

|

Humans had discovered metals. The first ones were those found in the native state, such as gold and copper. All metals known to the ancient world - gold, copper, silver, tin, lead, zinc and iron - were first used for beads (except tin, whose first known use is a bangle; get ready for an earlier tin bead).

Gold beads from Thailand.

|

|

|

|

It gets more complicated. In time, metals were more popular and people began searching for rocks that had just a hint of metal in them. They learned to crush the rocks and heat them and extract the metals.

Now we have smelting.

|

|

Then some genius decided that we could not only extract interesting materials, we could even make or synthesize them. The first synthetic material was faience, which for virtually all its life has been used mostly for beads.

We don't see faience much these days, but anciently it was a wonder.

|

|

|

|

The second synthetic was glass. Even more versatile than faience, for the first 2500 years of its production it was used all but exclusively for beads. Today we have many uses for glass, but the premiere bead material remains this marvelous stuff.

|

|

Nor has this process ended. The latest widely used smelted metal is aluminum. When first smelted at the end of the 19th century, it was more expensive than gold. It's first use: beads and jewelry.

Incidentally, two well-known landmarks were early aluminum products: the capstone of the Washington Monument in Washington, DC and the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus, London.

|

|

|

|

As for synthetic materials, the modern marvel is plastic. Developed simultaneously in the US and the UK, the Americans were looking for billiard ball ivory replacements. The English, on the other hand, made it to imitate tortoise shell jewelry.

|

|

For over eleven millennia many of the materials we take for granted were first made for or first used as bead materials.

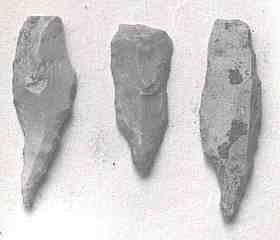

3. The Neolithic Revolution: Ground Stone Tools

The Neolithic ("New Stone Age") is often referred to as a "Revolution." That is because it was in this time (at least in some parts of the world) that people began to plant crops, domesticate animals, build villages and even develop surpluses and specialization. In other words, they were on their way to civilization.

The archaeological evidence for the Neolithic, the items that give it its name, are ground stone tools in place of chipped ones. Ground tools are more efficient than chipped ones, as they can be resharpened and they have a more predictable effect on whatever they are being used for.

|

Two of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Middle East are labeled "Proto-Neolithic" by their excavators, Ralph and Rose Solecki. Both are in the Shanidar Valley of Iraq and dated to about the same time as Lindenmeier, some 11,500 years ago.

|

|

|

|

On the valley floor is Zawi Chemi Shanidar, excavated by Rose and thought to be the summer home of the people. The beads were simple tubes made from bird bones (above) and river pebbles (right).

|

|

These, as well as stone beads found in the cave, were ground.

I measured the beginning and center of the holes as well as the distance between these points. This gave an idea of the tools used to drill the beads.

|

|

|

|

Unlike the beads, the drilling tools were not ground. They had been chipped, but not worked any further.

In other words, at the beginning of the period named for ground stone tools, beads were ground earlier than the tools.

|

|

4. The Neolithic Revolution: The Great Invention

Domesticating plants and animals and building villages were triumphs of this period. Other inventions introduced at this time included rotary motion and the bow and shaft.

|

|

One can turn materials into beads by treating them several ways. Some materials are naturally ready to be strung up, like these shells found at beaches. They have holes like those that people would put into them.

|

|

But most materials need to be drilled. I have conducted two series of experiments on shells using stone tools and found that there were several ways to form a hole.

I scratched at this clam for nearly 3 hours. After a depression was made, I found myself naturally doing half-turn rotary motions with my stone point.

|

|

|

|

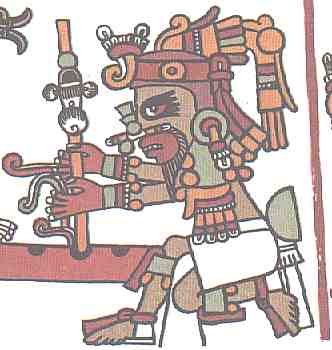

Hand-held drills are effective. In this scene from ancient Mexico the sacred fire is being relit after 52 years. All drilling scenes in the codices show hand drilling in deference to the fire-drilling ceremony, even though bow drills were employed for more practical applications, such as making beads, long before.

From The Codex Nuttal 1975, Dover, New York.

|

|

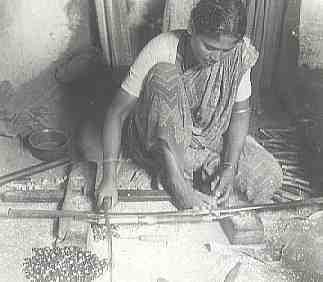

The bow drill has been used for a long time to make beads. No one knows exactly when that started, but it was an invention of the Neolithic Period.

A woman in Channapattinam, India makes wooden beads with a bow drill used as a lathe.

|

|

|

|

If the bow and drill is turned upwards you have another tool: the bow and arrow. This was the most important weapon for hunting and fighting for millennia, until gunpowder and guns came into use less than 1000 years ago.

From Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute 1974 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

|

|

The bow drill, the fire drill and the bow and arrow are essentially the same machine. Which came first? We may never know, but if experience is any guide, the bow drill for beads was most likely the first use of this configuration.

Summary

Yes, beads are pretty. They are decorative. They are ornamental. They even serve functions other than decoration. However, the point I want to make is that they are universally loved, desired and sought after. If people want something badly enough, they will work hard for it.

I suggest that:

- Much of the exploration of the world's surface (particularly inhospitable places) was done to find novel bead materials.

- The preparation of materials, including smelting and the making of synthetics, was initially done to produce raw materials to make into beads.

- The technological change from chipped to ground stone tools was preceded by the technology used to grind stone beads.

- The useful invention of the bow and shaft was likely a development of a means to more efficiently drill beads.

Beads are gems. They are worth working for, whether it takes hard exploration or hard thinking to come up with new raw materials or more efficient and attractive ways of

working them.

The bead story is not just that of pretty trinkets. It is interwoven into the story of the human race in ways we are only beginning to appreciate.

__________________________________________________

Small Bead Businesses | Beading & Beadwork | Ancient Beads | Trade Beads

Beadmaking & Materials | Bead Uses | Researching Beads | Beads and People

Center for Bead Research | Book Store | Free Store | Bead Bazaar

Shopping Mall | The Bead Auction | Galleries | People | Events

The Bead Site Home | Chat Line | Contact Us | Site Search Engine | FAQ

|

|